Author: Karris Jackson

In December 2016, I received a travel grant to attend the Global Summit on Community Philanthropy in Johannesburg, South Africa. The summit was hosted by the Global Fund for Community Foundations, a grassroots grantmaker working to promote and support institutions of community philanthropy around the world.

In December 2016, I received a travel grant to attend the Global Summit on Community Philanthropy in Johannesburg, South Africa. The summit was hosted by the Global Fund for Community Foundations, a grassroots grantmaker working to promote and support institutions of community philanthropy around the world.

I was interested in attending the conference because of its focus on shifting the power and resources of philanthropy closer to the community. I was also impressed with their 8 Pillars to #ShiftThePower Framework and excited to learn about innovative practices focused on giving power to people in community. The summit challenged me in a number of ways and several themes emerged for me as important to my work at POISE Foundation.

1. Justice as the Framework for Philanthropy

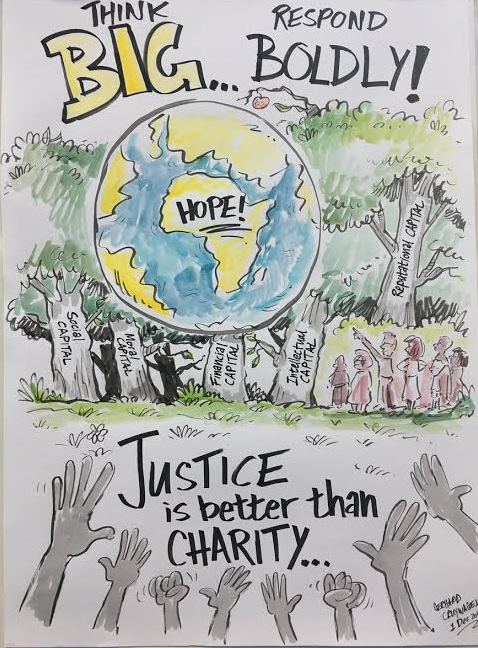

One of the highlights of the conference was a keynote address given by Ambassador James Joseph, President Emeritus of the Council on Foundations and former U.S. Ambassador to South Africa. His speech titled, Charity is Good but Justice is Better: Reimagining the Potential of Community Philanthropy, set the tone of the conference by lifting up the role of philanthropy in advancing a framework of justice. His plea to conference attendees to “Think Big and Act Boldly” was a consistent theme throughout the summit.

Good but Justice is Better: Reimagining the Potential of Community Philanthropy, set the tone of the conference by lifting up the role of philanthropy in advancing a framework of justice. His plea to conference attendees to “Think Big and Act Boldly” was a consistent theme throughout the summit.

2. Youth Philanthropy

I was impressed with the African Youth in Philanthropy Network and their goal of ensuring young people are involved in shaping the policies, practices, and broader inclusiveness in Africa’s development agenda. I was also impressed with their intentional focus on exposing youth across the African Continent to the important role of philanthropy from a local, regional, national, and international perspective.

3. Community Leadership

Throughout the conference, I learned about several community philanthropy initiatives that focus on investing in community leadership that is bold, bottom up, fluid, and innovative. One example was the Colonia Region Fund in Cologne, Uruguay. Its leadership is composed of citizens in the community. I was impressed by the resident’s deep commitment to the social, economic, and environmental sustainability of their community. Although the Fund was seeded by the Kellogg Foundation, community residents participate as donors to sustain the fund.

4. Leveraging ALL Forms of Capital

A theme throughout the conference was the importance of employing all forms of capital available to community philanthropy, not just financial. Ambassador James Joseph talked about SMIRF Capital (Social, Moral, Intellectual, Relational, and Financial). Often times we equate power with financial resources and several speakers lifted up the importance of leveraging other forms of capital to take power and demand justice in communities.

5. Innovation – New Structures

Rita Thapa, Founder of the Tewa-Nepal Women’s Fund, made a powerful statement when she said, “We can’t do good work from flawed structures.” She spoke about the need for community philanthropy to invent new structures and systems to get resources on the ground to the people that need it most. The Women’s Fund has more than 3,000 individual Nepali donors who embrace the value of local ownership and agency.

6. Participatory Grantmaking

Participatory Grantmaking was defined as grantmaking that places those directly impacted by the inequality at the center of the decision making (i.e. the community decides where the resources go). One example is the Edge Fund, which breaks down the usual power dynamics in funding by including the community, donors, and applicants in the decision making process.

7. Context Matters

Jenny Hodgson, Executive Director of Global Fund for Community Foundations, said, “We fund the things we recognize” (the corollary being that we are less likely to fund what we don’t recognize). The truth of this statement was highlighted again and again throughout my experience in South Africa. For example, I learned about organizations such as the Red Umbrella Fund which is the first global fund guided by and for sex workers to promote their human rights. I also learned about cultural rituals and practices that are different than my own. While riding through Maboneng in Johannesburg, I noticed underwear hanging from strings all throughout the neighborhood. I couldn’t understand why someone would hang women’s underwear throughout their community. I later learned that the underwear represented the onset of the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence. There were 3,600 pairs of underwear hanging up on clotheslines to represent the 3,600 women who are raped throughout South Africa every day.

Learning about organizations like Red Umbrella and the 16 Days of Activism underscored the idea that context matters. It challenged me to consider how my own experiences and cultural norms influence the way I lead grantmaking in my institution. If I only fund the things I recognize and are familiar with, how can I effectively employ grantmaking in communities and cultures that are different than my own?

Conclusion

My experience in South Africa challenged me to think critically about the inherent contradictions presented by philanthropic institutions. During one of our long breaks, I decided to go out for a walk in the bustling community surrounding Turbine Hall in Johannesburg. When I asked a conference volunteer about where to walk, she said, “You can’t leave the gated area, it’s dangerous out there.” I didn’t think I heard her correctly, but when I asked her again, she repeated the same thing. I was shocked. I was at a conference where we were talking about people-based development and shifting power and resources closer to the community, and the volunteer told me to stay inside the gate. At that point, I noticed the facility was built back, far from the street, and surrounded by a tall gate, with a guard standing outside: we were completely disconnected from the community. I also realized that the entire conference was somewhat disconnected from the community: there were no site visits and no intentional connections to the indigenous people in Johannesburg. To me, this symbolized the contradictions that plague institutional philanthropy. There’s always a “gate” that separates philanthropy from the people it wants to serve.

I learned a lot at the summit and traveling to South Africa was an amazing experience, but I left with more questions than answers – questions that can apply to philanthropy anywhere in the world:

- Is it possible for me to suspend my own privilege and assumptions to fund programs and project that “I don’t know and don’t understand”?

- What happens when the solutions a community requests support for are different from the solutions I want to fund? What if I don’t morally agree with what they want to do?

- Can institutional philanthropy ever shift resources and power closer to communities when their board members and staff members oftentimes have no lived experience in the communities they serve? Is it possible to dismantle the gate that separates institutional philanthropy from community?

Karris Jackson is Vice President of Programs at the POISE Foundation. If you would like to learn more about the Global Summit, discuss Karris' insights with her, or see more amazing pictures from her trip, please let us know and we'll connect you with her.